7 minutes

Velociraptor Threathunting - Quick Introduction

In my previous posts, I demonstrated how to use Velociraptor to extract artefacts from dead hosts. However, the real strength of Velociraptor lies in its ability to conduct searches across multiple hosts for artefacts. This is particularly useful when responders are trying to answer questions such as, “Are there baddies in the network?” “How many machines have executable X on them?” and “Did user X log on to system Y?” In this blog post, I will provide a quick introduction to using Velociraptor to address these types of questions.

Quick intro to VQL

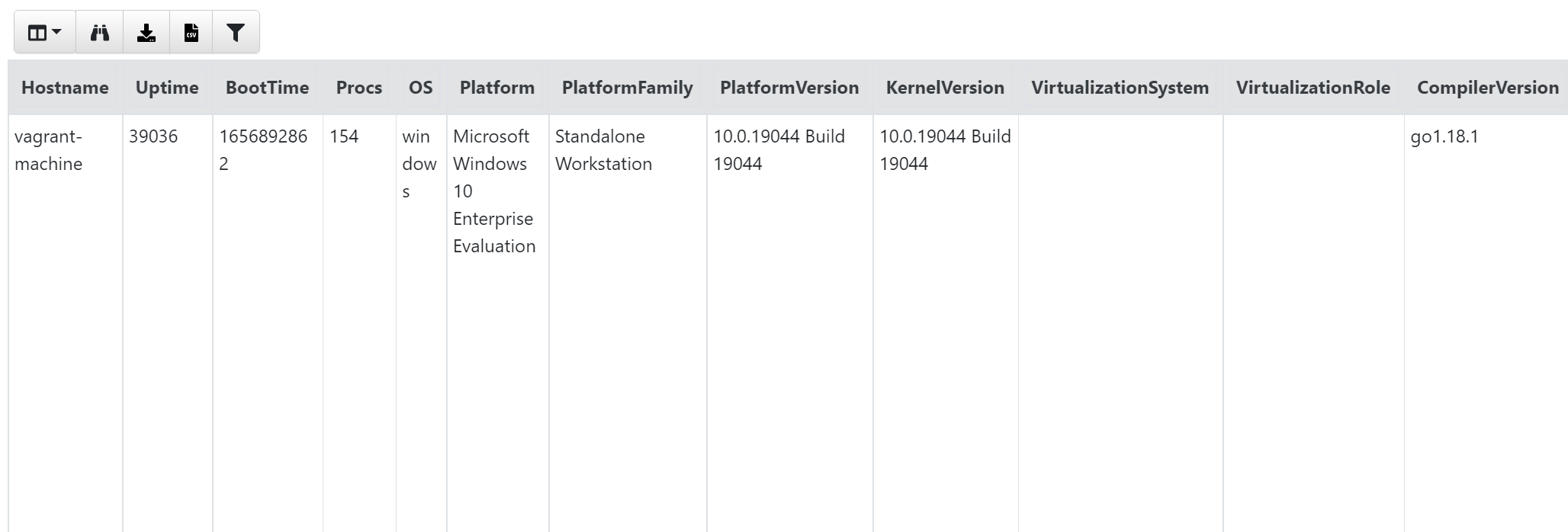

All queries the Velociraptor performs are executed using the Velociraptor Query Language, or VQL, which is essentially a simpler version of SQL. Therefore, most people should find it easy to read and learn. For instance, the query below retrieves all columns from the Info() artefacts and presents them to the responder.

SELECT * FROM info()

The output will resemble something like this:

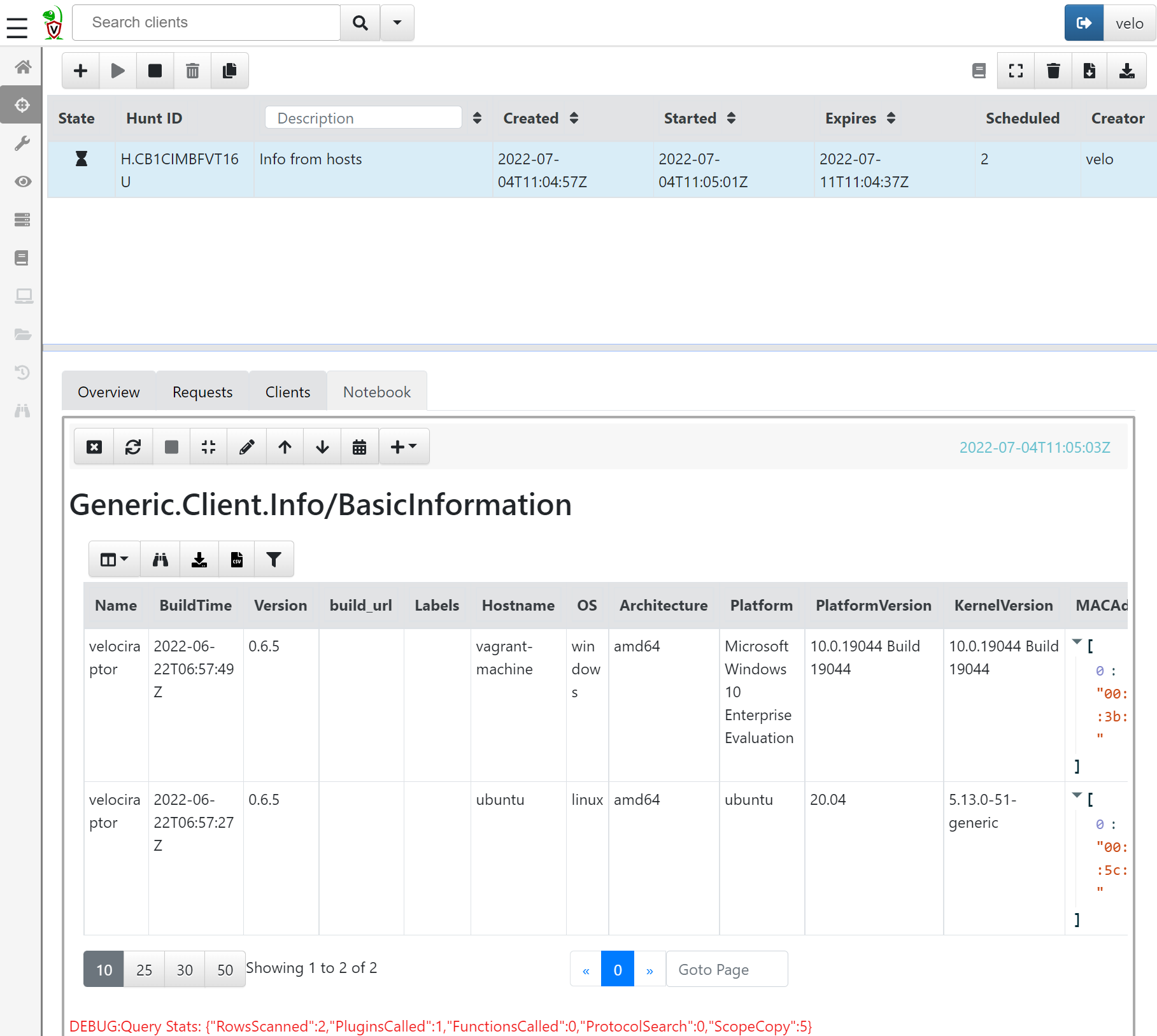

If you perform this across multiple machines using the ‘Hunt Manager’ in Velociraptor, you can expand the query to get an overview of how many different versions of OS you have. To do this, we will create a hunt using the Generic.Client.Info artefacts and query that across all machines. Once it’s done, the information received can be seen in the ‘Notebook’ tab of the hunt:

Now, this will provide a table with a row for each machine, which can be handy. However, if there are 1000 endpoints in the environment, the table may not be very easy to overview. Therefore, let’s edit the VQL statement to enhance readability. To do this, press the small edit button at the top of the notebook. The default query will likely resemble something like this:

/*

# Generic.Client.Info/BasicInformation

*/

SELECT * FROM source(artifact="Generic.Client.Info/BasicInformation")

LIMIT 50

If we examine the statement, we will observe that the data source is not info(); rather, it is source(). This is because it originates from a hunt collecting artefacts across multiple machines, rather than a single run on one machine.

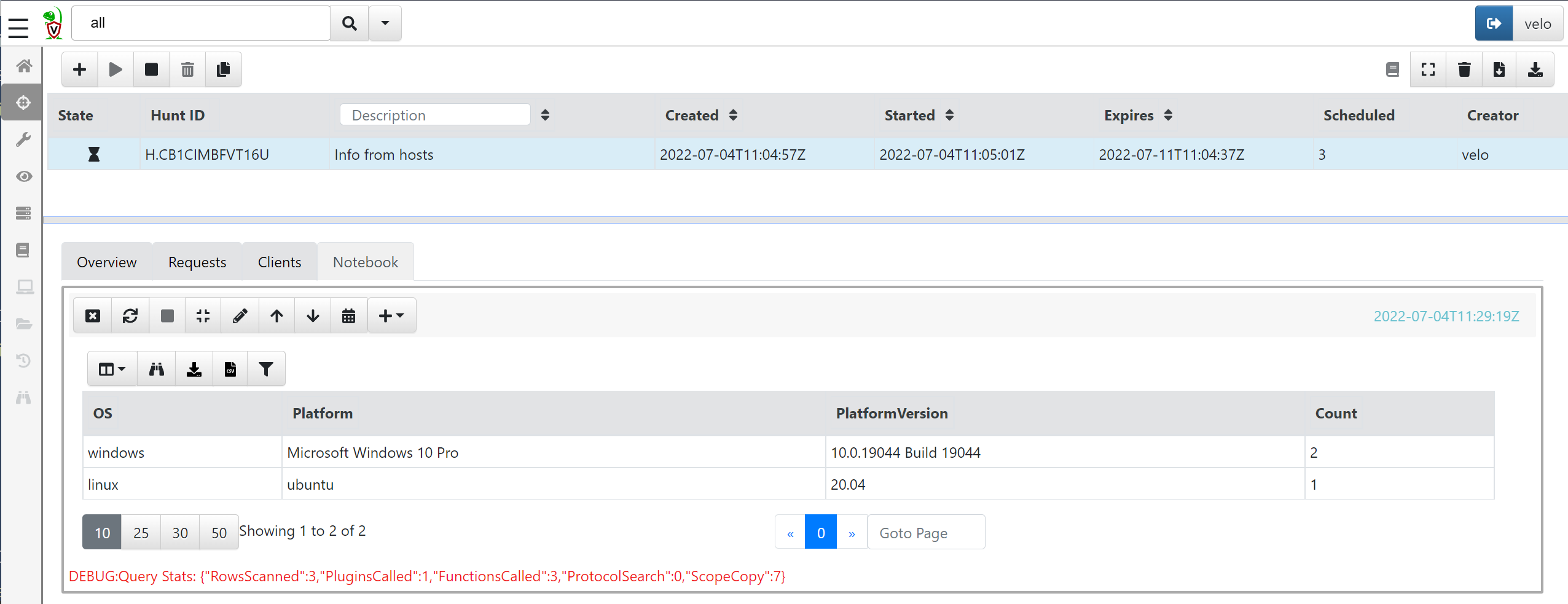

Now, to get an overview, let’s change the VQL statement to:

SELECT OS,Platform,PlatformVersion,count() AS Count FROM source()

GROUP BY OS

The output is that we now have a row for each OS version and a count of how many systems have that OS:

As you can see, the VQL language is quite powerful and provides the responder with the ability to quickly collect data or to gain an overview of the data collected from hosts. In fact, all hunts in Velociraptor are actually VQL statements made to query systems for information.

Installing artefacts from ‘Artifact Exchange’

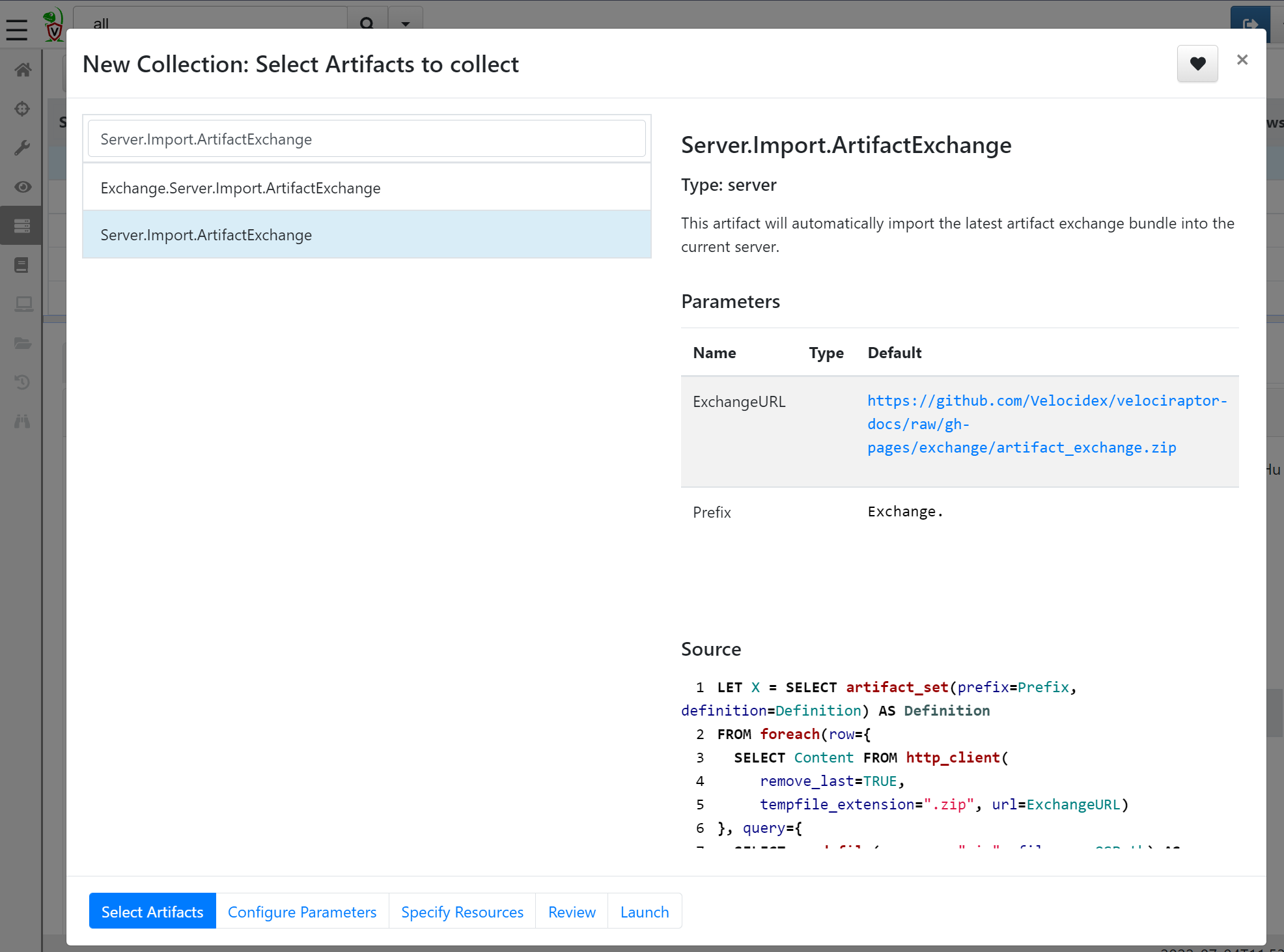

There are many artefacts already built into Velociraptor, but a really neat feature of the entire Velociraptor universe is the Artifact Exchange. The exchange is a collection of artefacts contributed by the community. This means that if you are using Velociraptor and make an amazing query that is not already part of the standard system, you can submit it to the exchange and share it with everyone else so they can benefit from it and discover even more interesting things in environments.

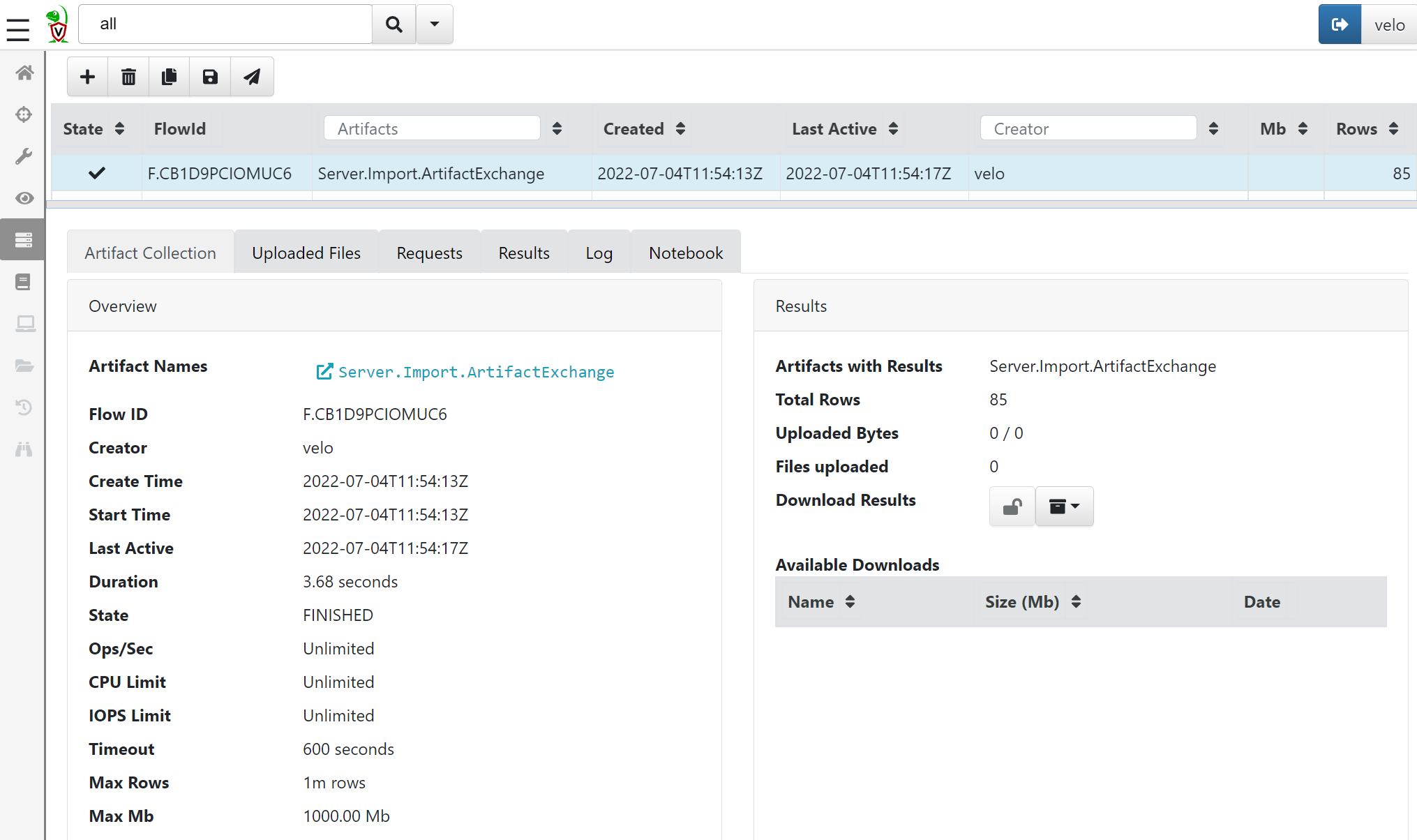

The ‘Artifact Exchange’ needs to be imported into the Velociraptor server. This can be done by running the artefact Server.Import.ArtifactExchange directly on the Velociraptor server. Navigate to the ‘Server Artifact’ menu and create a new collection. From the dropdown menu, select the Server.Import.ArtifactExchange artefact and press launch:

All artifacts from the exchange are now imported into the server and can be used in hunts.

Hunting

Now that we have scratched the surface of VQL and how to use it in hunts, let’s delve into some of the more powerful applications of hunts and VQL in Velociraptor. This section is a collection of different hunts that I have found useful and would like to share.

Finding renamed executables

One thing we often observe in cases is the use of psexec or the utilization of LOLBINs, for example: employing rundll32.exe to execute a dll on the host. Security programs sometimes block these methods to prevent threat actors from executing arbitrary code on the systems, prompting them to discover ingenious ways to evade detection. One such method is copying the executable to another location.

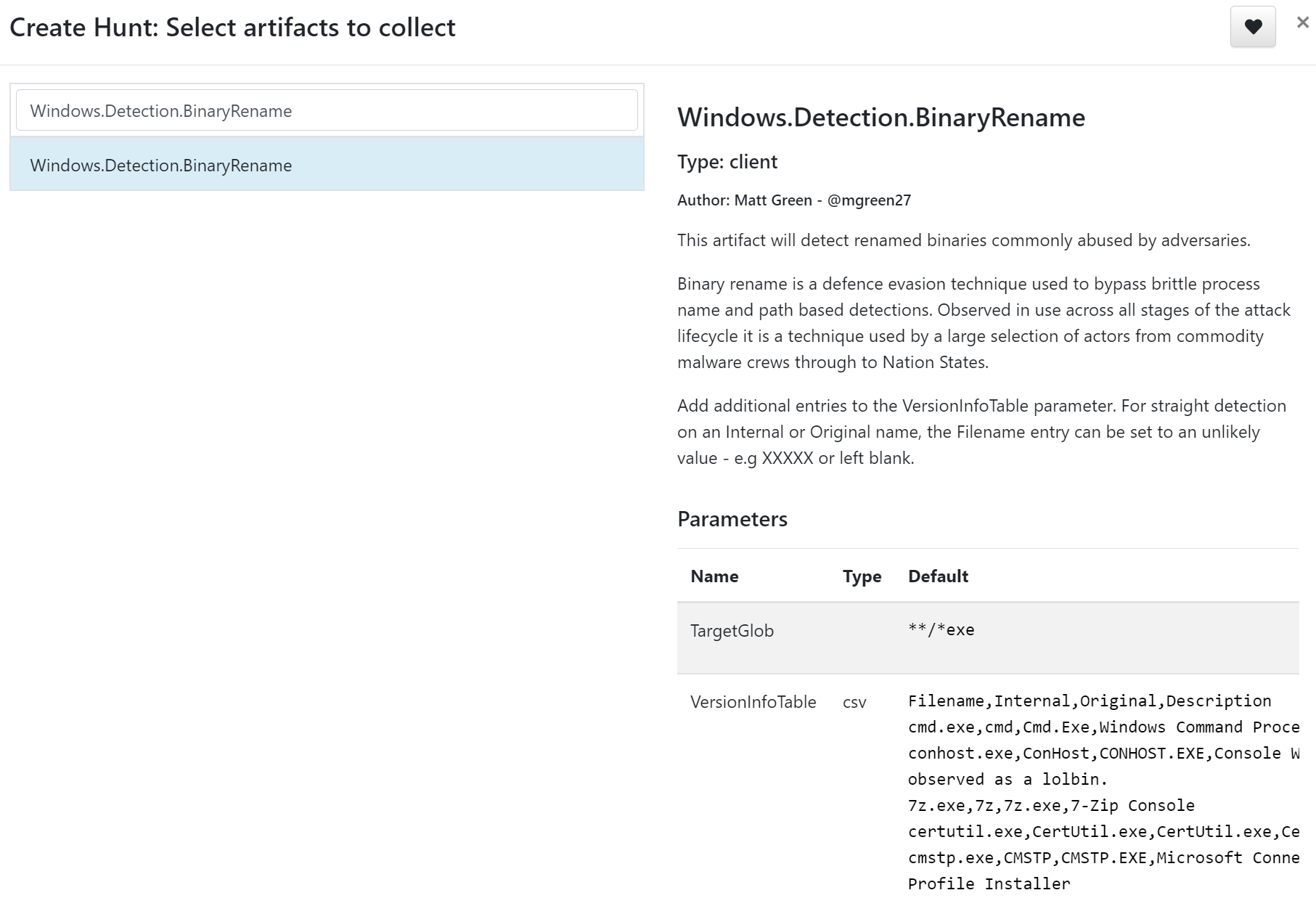

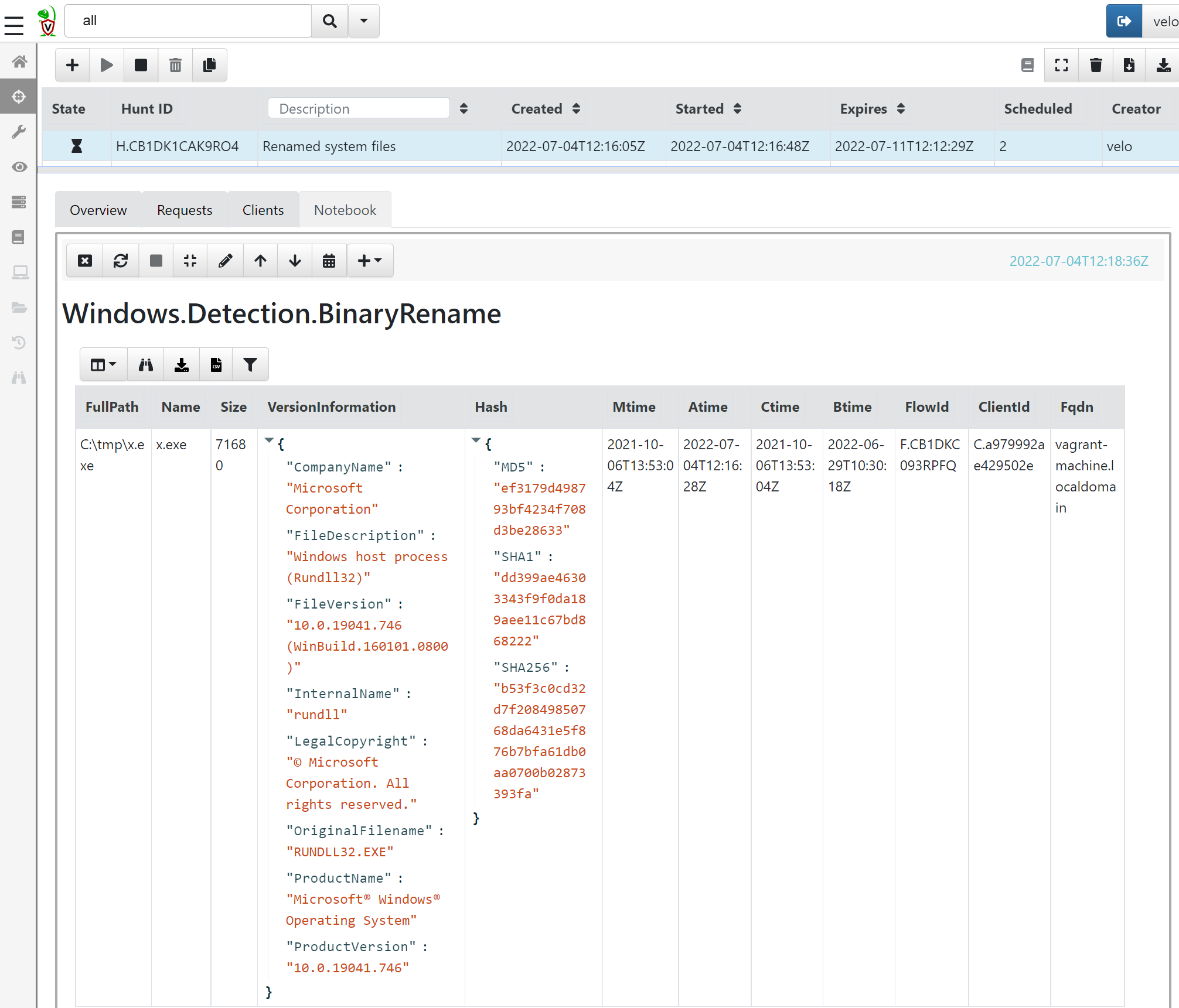

For example, let’s say a threat actor is avoiding detection by renaming rundll32.exe to x.exe and moving the renamed file to C:\tmp. To find that using Velociraptor, we can use the artefacts called Windows.Detection.BinaryRename, which will search for executables and compare the binary metadata against a predefined list (which you can add to or remove from):

Results:

Finding lateral movement

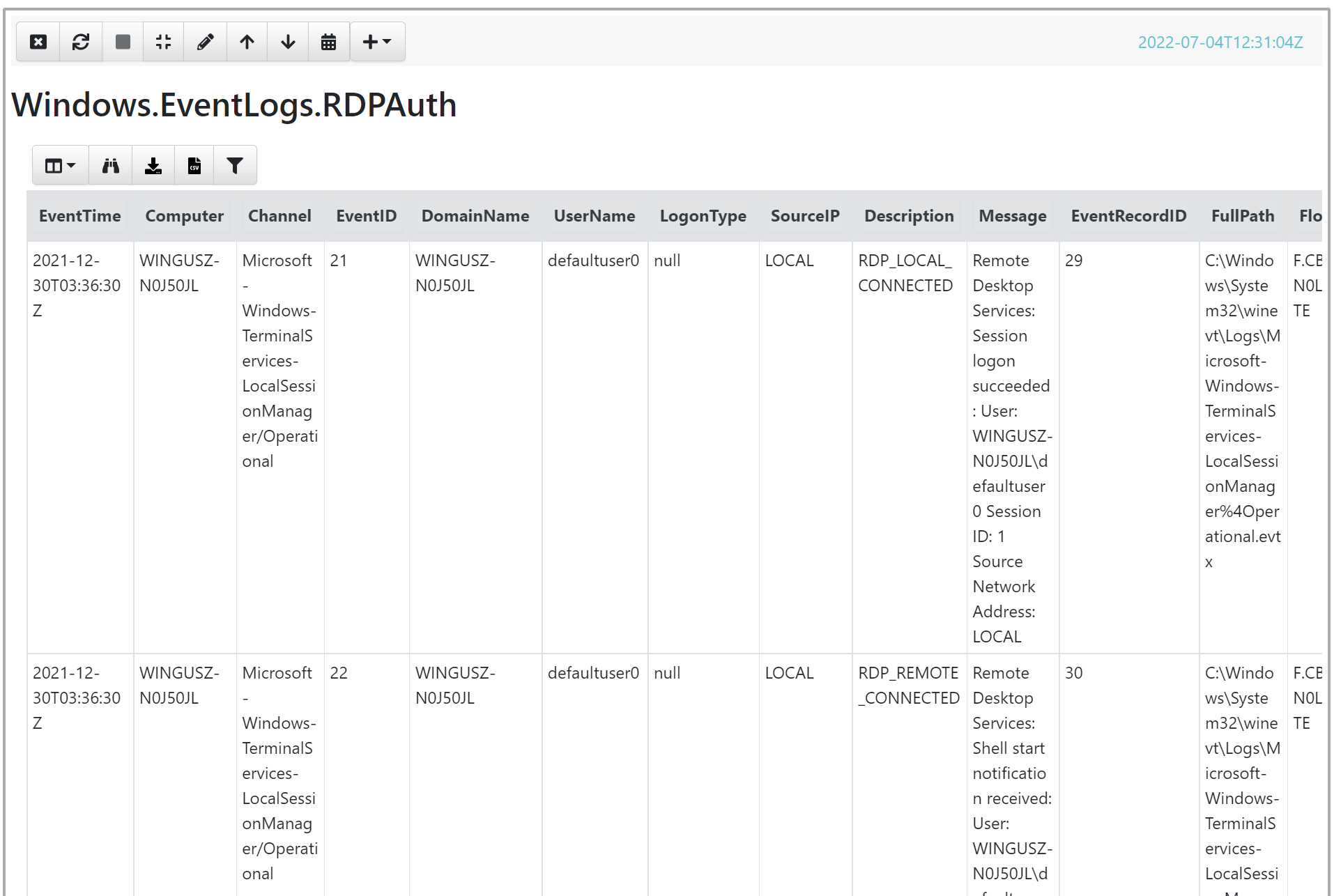

A key question in nearly all investigations and hunts is: ‘Where did the threat actor go?’ To answer this question—or to obtain an indication—we can utilize the artefact Windows.EventLogs-RDPAuth.

Although the name suggests that Velociraptor solely searches for RDP authentications, a closer look at the artifact reveals that its description indicates it also examines common logons, such as types 3, 7, and 10 of event 4624, which are not exclusively associated with RDP authentication.

As you can see, the output can be quite noisy and difficult to grasp an overview of:

To narrow down the output, let’s edit the VQL statement:

SELECT EventTime,Computer,Channel,EventID,UserName,LogonType,SourceIP,Description,Message,Fqdn FROM source()

WHERE ( // excluded logons of the user on their own system

(UserName =~ "suspect1" AND NOT Computer =~ "suspect1workstation")

)

AND NOT EventID = 4634 // less interested in logoff events

// Remove DCs, exchange and fileserver, since this is expected to have alot of logons

AND NOT (Computer =~ "dc" OR Computer =~ "exchange" OR Computer =~ "fs1")

ORDER BY EventTime

The output should be a more concise list of logons to other hosts from the patient zero user account, providing the responder with an easier overview of where to investigate next.

Getting a list of running processes

An important thing to always keep in mind when doing threat hunts and investigations is, “What does normal look like?” It’s always tough to answer that question as a consultant coming into an environment, but Velociraptor can help provide an overview of what’s running on the systems.

To obtain a list of running processes, we can use the artefact Windows.System.Pslist. The output will be quite large, so it makes sense to sort and stack the results.

The following VQL query retrieves the output from the hunt and displays only the unsigned binaries running on the systems:

SELECT Name,Exe,Commandline,Hash.SHA256 AS SHA256,Authenticode.Trusted,Username,Fqdn,count() AS Count FROM source()

WHERE Authenticode.Trusted = "untrusted" //show only unsigned binaries

AND NOT Exe = "C:\\Path\\to\\whitelisted\\binary"

//Stack for prevalence

GROUP BY Exe

ORDER BY Count

Finding files across the network

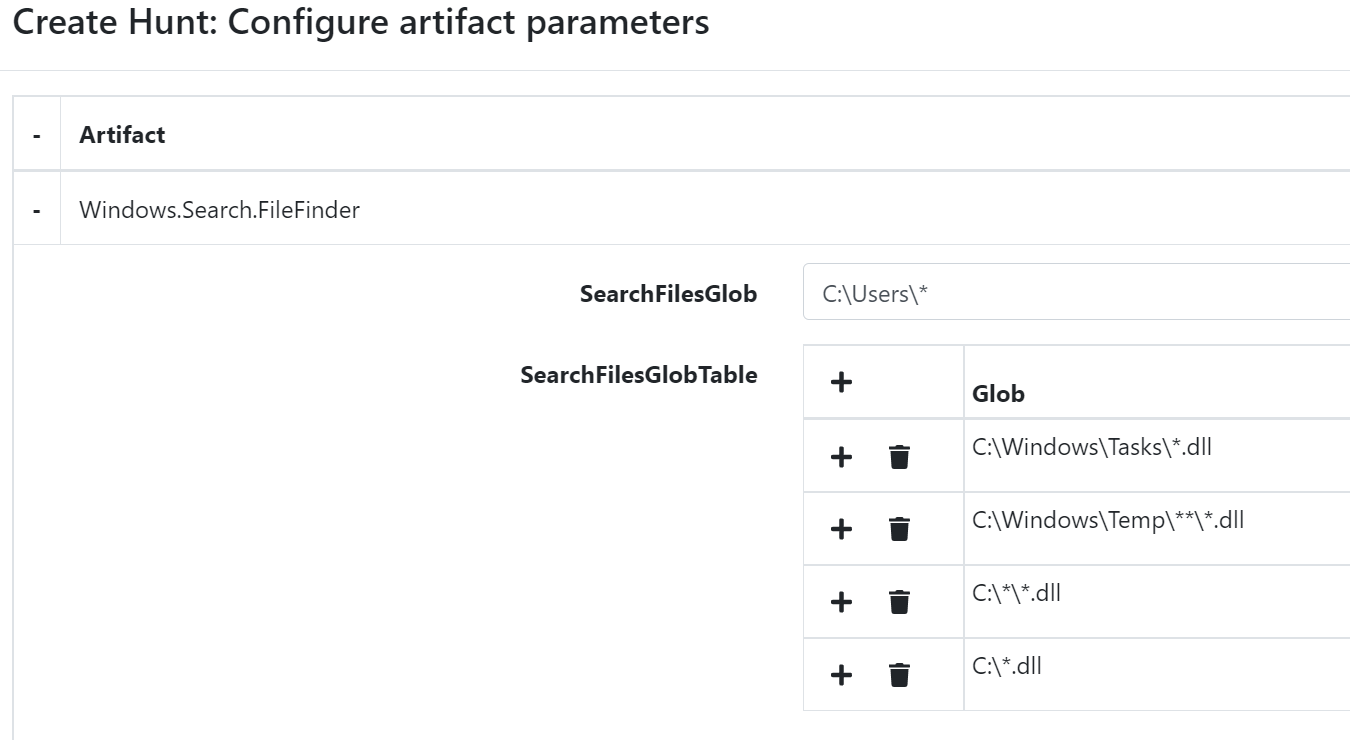

The last artefact I would like to show is how to search for files. This can be useful if we already have a list of known IOCs with filenames that we want to look for, or if we are simply hunting for ‘weird’ files. To search for files, we can use the Windows.Search.FileFinder artefact.

As an example, let’s search for DLL files in unusual locations that might help us find problematic items. For the SearchFileGlobTable, we will add locations to search for:

C:\Windows\Tasks\*.dll

C:\Windows\Temp\**\*.dll

C:\*\*.dll

C:\*.dll

The output can be very noisy, and we will therefore need to sort in the VQL statement to make it a bit easier to read:

SELECT Fqdn,FullPath,MTime as Modified,BTime as Created,IsDir, count() as Count FROM source() WHERE IsDir = 'false'

GROUP BY FullPath

ORDER BY Count

Summary

As you can see, the Velociraptor agent can be used to perform very powerful and quick searches across the entire host landscape, making it easier for threat hunters and others to identify things that are out of the ordinary.

For more information about how to conduct hunts and create queries in VQL, please see the Velociraptor documentation.

Credit

Sources for this blog post comes from:

- Stephan Berger twitter

- Matthew Green twitter

- Eric Capuano’s awesome Velociraptor video and the Velociraptor notebook